An unusually useless week, this one. I ended up spending a lot of it trying to figure out Exalted 3E. Which, to be sure, is something I kind of feel like I ought to do, because Exalted is another one of those games that I spent a lot of years absolutely obsessed with – buying every supplement, trying to internalise the intended style of play, lecturing people on the lore. Like most things, I ultimately had to realise that it had some serious flaws, but still… it’s definitely the shiniest game I’ve ever seen.

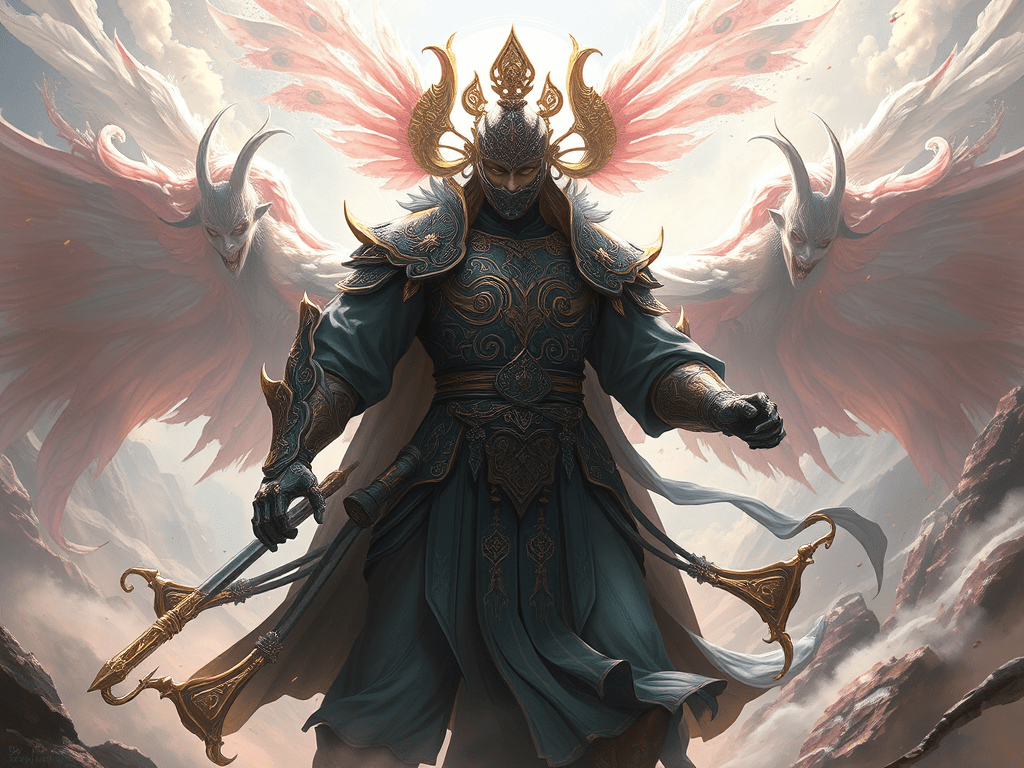

To summarise something very complicated, Exalted is a game set in a world that combines wuxia, anime, sword & sorcery and ancient myth, full of larger-than-life heroes, bizarre spirits, exotic cultures, and characters with names like “the Lover Clad in the Raiment of Tears.” It’s at once over the top and oddly gritty and rooted in practical realities – which is a contradiction that a lot of people have tried to figure out how to deal with.

The system for Exalted has, over the course of its three editions, been seen as very frustrating to play. I think the best way I’ve ever heard someone describe it was, “a game of cinematic action, played in slow motion.” There are always a thousand nitpicky rules to apply, most of them for things that probably aren’t even going to have any practical difference – when you’re rolling 20 dice to attack, having a -1 penalty is unlikely to matter, but that doesn’t stop the rules from demanding that you apply it.

With of course the high-minded declaration that “well, if you think any rule is too bothersome, just ignore it!” Yeah, great, thanks. The problem is, the rules in a system all fit together, and there are consequences in unexpected places when you just throw one out. To change one part of a system, you have to go over the whole system and modify it to work without that part… and once you’re doing that, you start to feel like you might as well write your own rule system from scratch.

(and yes, I have tried writing a port of Exalted. It’s… still very much a work in progress, let’s say)

So what about the third edition, in my esteemed opinion? Well… it fixes a few things that needed fixing, but those things add even more complexity. The two major systems that I’ve read up on are combat and social influence, and I actually really like the idea behind them, but I still have no idea how they play in practice.

For combat, attacks are divided into withering and decisive. Successful withering attacks let you build up a pool of damage dice while reducing the dice in your opponent’s pool, which you can then deliver with a successful decisive attack – effectively, you fence-fence-fence, going back and forth, until one of you manage to gain the advantage and deliver an actual bleeding wound. That, given how punishing injury is in this system, might well mean the end of the fight. Which does make more sense than how it worked back in second edition, where combat just tended to last until the first time someone landed a successful blow, at which point the other person usually turned into a fine red mist.

Social influence, meanwhile, is… genuinely kind of impressive in theory. The fundamental premise is that in order to talk someone into doing something, you must either offer a tempting bribe, deliver a credible threat, or play on one of the mark’s existing beliefs or hang-ups (called intimacies in this system). Intimacies come in different strength, and how large a favour you can get the target to do for you depends on how strong an intimacy you can piggy-back it on. So basically, you can only make someone do something that is, to some extent, in character for them to do. “So, I understand that Lord Smiling Crane is no particular friend of yours? I just so happen to have a plan that would humiliate him…”

To tailor your argument correctly, you of course have to know what a mark’s intimacies are, which can be found out with a special roll. However, this roll, too, has to be supported by what is actually going on in the game – for instance, you can see two people talking, and roll to find out if they have any strong feelings regarding each other, but you can’t discover their sentiments about something entirely unrelated without seeing how they interact with it at least as a concept.

You can create intimacies in people, again with a roll, but those are limited – an intimacy that is not supported by a previously existing intimacy is always going to be of the weakest order, so you can’t just custom-make a strong conviction that will be convenient to you. It’s more like, you can chat someone up for a while, share a few laughs, buy them a drink, and then roll to create a weak intimacy of friendship for you in them. Then you can use that one to get them to do you a small favour, since you’re getting along so well… but again, a minor intimacy is only good for a minor favour.

Now, I actually think this all sounds pretty good. It seems to simulate a way of talking people around that I can see happening. It makes smooth talkers potentially very dangerous, but it requires them to be clever and figure out the right strings to pull. And that’s actually very exciting for me, because if it actually works in practice, then this might just be the first functional social system I’ve ever run across.

I’ll believe it when I see it at my table, though.

Leave a comment